LSL #nbitsLogical shift left bynbits.LSR #nbitsLogical shift right bynbits.ASR #nbitsArithmetic shift right bynbits, keeping signed bit on the left.ROR #nbitsRotate right bynbits.

MOV can move into register only 16-bit at a time. So to load a 64-bit value, we need to shift a maximum of 4 times with MOVK.

MOV Xd, #imm16 moves imm16 into Xd

MOVK Xd, #imm16 moves imm16 into Xd while keeping original data in Xd

MOVK Xd, #imm16, LSL #4 logical shift left imm16 by 4-bits

MOVN Xd, #imm16 moves logical NOT of imm16 into Xd

The basic form of ADD and SUB adds/substracts Xs with Operand2, then store the result in Xd.

ADD{S} Xd, Xs, Operand2

ADC{S} Xd, Xs, Operand2

SUB{S} Xd, Xs, Operand2

SBC{S} Xd, Xs, Operant2There are cases where a number might be greater than 64-bit, so we need multiple registers. ADDS and SUBS does the same work as ADD and SUB, but also adds a carry/borrow condition in the NZCV register.

Think about carry and borrow in arithmetic. The NZCV register is the 1 when you do carry/borrow.

The ADC/SBC works based on the previous ADDS/SUBS carry/borrow condition. The ADCS/SBCS sets the carry/borrow just like ADDS/SUBS.

Example:

// Simple addition/subtraction with one register sized-number

ADD X0, X1, #4 // X0 = X1 + 4

SUB X2, X3, X4 // X2 = X3 - X4

// Adding and subtracting a 192-bit number

ADDS X0, X3, #1 // Add lower bits and set carry

ADCS X1, X4, #1 // Add middle bits with carry, and set a new carry

ADC X2, X5, #1 // Add higher bits with carry

SUBS X0, X3, #1 // Subtract lower bits and set borrow

SBCS X1, X4, #1 // Subtract middle bits with borrow, and set a new carry

SBC X2, X5, #1 // Subtract higher bits with borrowComparisons, ADDS/SUBS, or S-variant logical operators sets the NZCV register (CPSR in ARM) used for branching.

| Suffix | Flags | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| EQ | Z set | Equal |

| NE | Z clear | Not equal |

| CS or HS | C set | Higher or same (unsigned >=) |

| CC or LO | C clear | Lower (unsigned <) |

| MI | N set | Negative |

| PL | N clear | Positive or zero |

| VS | V set | Overflow |

| VC | V clear | No overflow |

| HI | C set and Z clear | Higher (unsigned >) |

| LS | C clear or Z set | Lower or same (unsigned <=) |

| GE | N and V the same | Signed >= |

| LT | N and V differ | Signed < |

| GT | Z clear, N and V the same | Signed > |

| LE | Z set, N and V differ | Signed <= |

| AL | Any | Always. This suffix is normally omitted. |

MUL only saves the lower 64-bit of the multiplication from two 64-bit registers:

// Multiply Xn by Xm and store the lower 64-bit in Xd

MUL Xd, Xn, XmSMULH and UMULH saves the upper 64-bit of multiplication:

// Signed upper 64-bit

SMULH Xd, Xn, Xm

// Unsigned upper 64-bit

UMULH Xd, Xn, XmMultiply two 32-bit registers and store full result in 64-bit register:

// Signed

SMULL Xd, Wn, Wm

// Unsigned

UMULL Xd, Wn, WmNegatives of multiplication:

// Calculates -(Xn * Xm)

MNEG Xd, Xn, Xm

// Signed 32-bit version

SMNEGL Xd, Wn, Wm

// Unsigned 32-bit version

UMNEGL Xd, Wn, WmDoes multiplication with accumulation:

ADDones:Xd = Xa + Xn * XmSUBones:Xd = Xa - Xn * XmXacan be the same asXd- Similarly for

Wregister ones

MADD Xd, Xn, Xm, Xa

MSUB Xd, Xn, Xm, Xa

// 32-bit variants

SMADDL Xd, Wn, Wm, Xa

UMADDL Xd, Wn, Wm, Xa

SMSUBL Xd, Wn, Wm, Xa

UMSUBL Xd, Wn, Wm, Xa// Signed divide Xn by Xm and store in Xd

SDIV Xd, Xn, Xm

// Unsigned divide Xn by Xm and store in Xd

UDIV Xd, Xn, XmDivide doesn’t throw division by zero error, but just returns 0.

Condition is bad for performance!

Usually CMP comparing two registers by substraction.

CMN: Uses addition instead of subtraction.

TST: Performs a bitwise AND operation between Xn and Operand2.

Comparison stores the result in the NZCV register, to be used later with branching instruction.

Branching retrieves the NZCV registers value and performs condition based on it.

// Jump to branch without testing condition

B branch_name

// Jump to function

BL function_nameCMP X1, X2 // Or SUBS X2, X2, #1, which means testing if X2 reaches 0

// Use comparison value stored in NZCV register to determine condition

B.{condition} branch_name

cont:

// continue

branch_name:

// Do some work in branch

B cont // Go to cont// W2-- until W2 is 0

loop:

SUBS W2, W2, #1 // Note the S at the end of SUBS

B.NE loop // Go to loop if not equalAND is useful for masking bits with Operand2, ORR is useful for setting bits.

S variant sets the NZDV register.

AND{S} Xd, Xs, Operand2 // Bitwise AND between Xs and Operand2

EOR{S} Xd, Xs, Operand2 // Bitwise XOR between Xs and Operand2

ORR{S} Xd, Xs, Operand2 // Bitwise OR between Xs and Operand2

BIC{S} Xd, Xs, Operand2 // Bitwise Xs AND NOT Operand2Two ways of importing:

- Include: In main, use

.include "file.s". The file won’t need to be assembled to.ofile. - Assemble then link:

.global func_namemakesfunc_namefunction available for other programs.

Only one program can be called_start.

gcc compiles .S file with C-style includes with capital S.

Good for performance, bad for conserving memory.

Inserts copy of the code at every point used, so no need to push/pop stack.

Example:

.MACRO macroname parameter1, parameter2,...

2:

// Some work

B.NE 2b

B 1f

// ...

1:

// Some other work

.ENDMIf macro is used multiple times, duplicate text labels will create conflict. ARM allows using duplicate numeric labels like 1, 2, 3…

e.g.:

2b– label 2 in backward direction1f– label 1 in forward direction

Bad for performance, good for conserving memory. Usually needs to push/pop stack when calling.

BL func_name calls the func_name function.

RET in the function returns with result in X0 register.

Registers:

X0-X7– Argument registers. Function parameters that can be used by the function.X0-X18might be corrupted after running the function, so any value must be saved to stack before calling function.X19-X30– Callee-saved registers. Caller assumes they stay unchanged. If used by the function, must be saved within the function and restored before return.LRstores where the next instruction is after function, so must be saved to stack if calling a nested function within the function.- Calling

RETresumes execution from currentLRpointed instruction.

- Calling

See Page 143 ARM 64 assembly book

Using Extern

When you use it as an extern, e.g.:

extern int mytoupper( char *, char * );- The first

char*input goes toX0, the secondchar*input goes toX1, and so on… - The returned int goes to

X0

Using Inline

When you use it inline, e.g.:

__asm__ volatile(

"mov X3, %2\n"

"loop:\n"

"LDRB W4, [%1], #1\n"

"CMP W4, #'A'\n"

// ...

"SUB %0, %2, X3\n"

: "=r"(len) // OutputOperands: "=r"(len) means write to operand, corresponds to %0 in the asm

: "r"(str), "r"(outBuf) // InputOperands: "r"(str) means input with variable "str". str and outBuf corresponds to %1 and %2 in the asm

: "r3", "r4"); // Clobbers: registers that might be used by the asm so C compiler will avoid (note it is r not X or W)- The output is aliased as

%0 - The input variables start from

%1,%2, and so on…

IMPORTANT: Pointer vs Value

LDR Xd, =labelorSTR Xd, =labelloads/stores from pointer from/to the label addressLDR Xd, labelorSTR Xd, labelloads/stores directly from/to the label’s contentUse pointer for strings, arrays, etc. just like you use it in C.

Square bracket on [Xn] signifies load from the memory address stored in Xn, not the register content of Xn.

Even though the stack grows downward, the memory save and load instructions access low -> high memory address.

// Load the address of mynumber into X1 (X1 is a pointer)

LDR X1, =mynumber

// Load mynumber pointed to by X1 into X2

LDR X2, [X1]

// Or load mynumber's value directly into X2

LDR X2, number

.data

mynumber: .quad 0x123456789ABCDEF0To load types other than word or quad, and pad correctly:

LDR{type} Xt, [Xa] // Xa is a pointer to the addressType can be one of the following:

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| B | Unsigned byte |

| SB | Signed byte |

| H | Unsigned halfword (16 bits) |

| SH | Signed halfword (16 bits) |

| SW | Signed word |

-

Pre-indexing:

STP LR, FP, [SP, #-16]!Memory address updated

SPis first updated toSP = SP - 16- Then

LRandFPare stored in increasing memory address from the newSPaddress (LR -> [SP]andFP -> [SP + #8])

-

Post-indexing:

LDR LR, FP, [SP], #16Memory accessed first

LRandFPare loaded fromSPandSP + 8- Then SP is updated to

SP = SP + 16after the memory operation

Example:

// Assume X0 = 0x1000

// Load memory content from 0x1000 + 16 = 0x1010 to 0x1017

LDR X1, [X0, #16]

// Update X0 to 0x1010, then load memory content from 0x1010 to 0x1017

LDR X1, [X0, #16]!

// Load memory from 0x1000-0x1008, then update X0 to 0x1010

LDR X1, [X0], #16

// Similarly for STR operationsStack Pointer (SP) grows downwards by 16 byte aligned on ARM. Non-16-byte aligned address will crash.

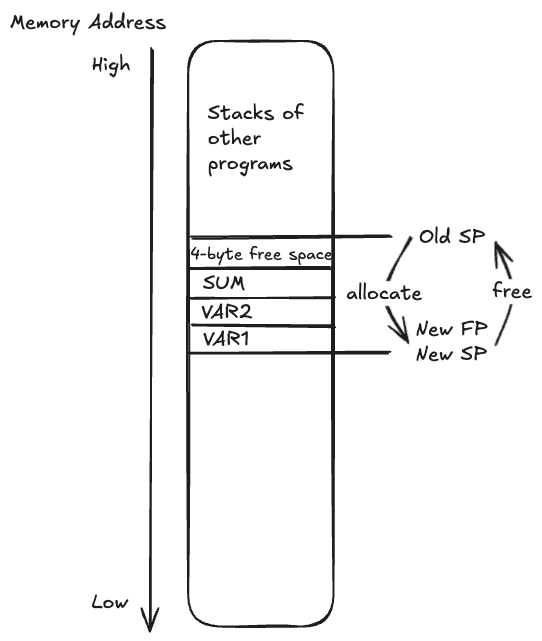

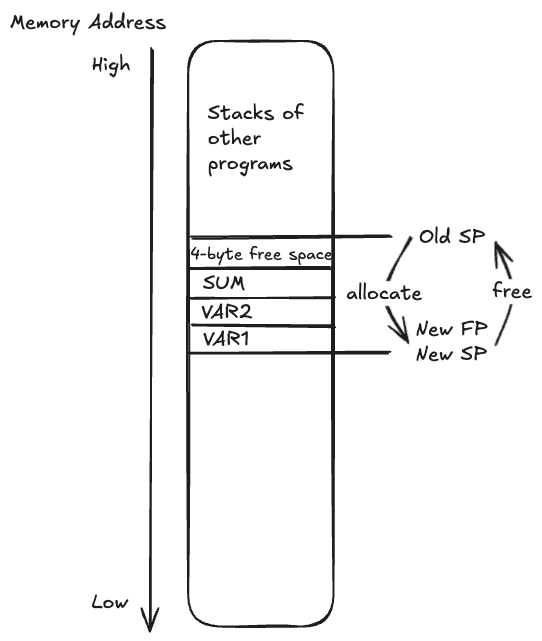

Wastes memory if variables are not using all 16-byte, can be addressed by using Frame Pointer (FP)

Note there seems to be discrepancy between what is described in the book and online about whether FP should match SP or be at an offset. Here we follow the book. See this StackOverflow Discussion.

X29 register is aliased as Frame Pointer (FP), and set address relative to FP

// Assume SP = 0x1000

// Positive memory offsets relative to FP

.EQU VAR1, 0

.EQU VAR2, 4

.EQU SUM, 8

SUB FP, SP, #16

SUB SP, SP, #16

// Now FP == SP are both 0x0FF0

// Address 0x0FF0 - 0x0FFF can be used

LDR W4, [FP, #VAR1] // W4 loads from 0x0FF0

LDR W5, [FP, #VAR2] // W5 loads from 0x0FF4

SUM W6, W4, W5

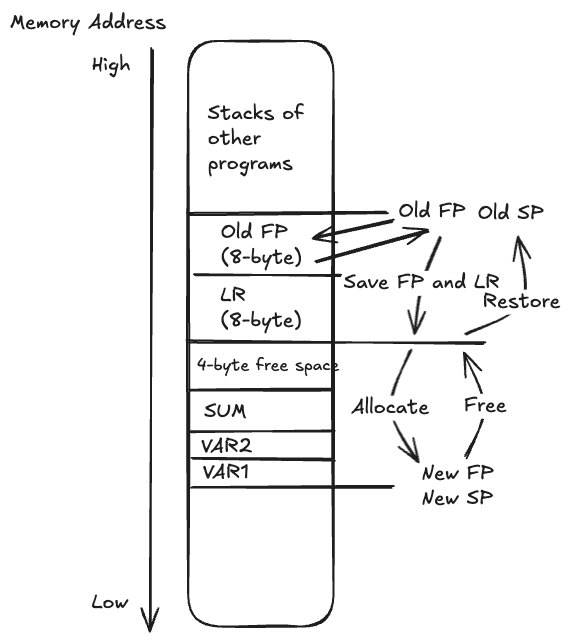

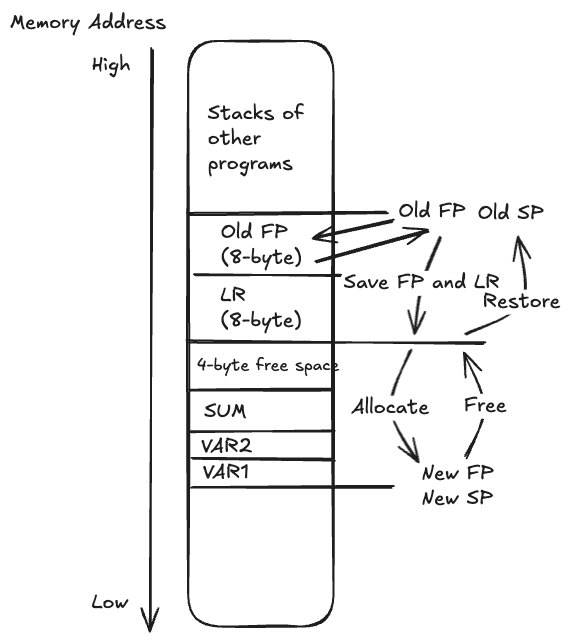

STR W6, [FP, #SUM] // Store sum at 0x0FF8Save LR and previous program’s FP with the first 16-byte:

// Assume SP = 0x1000, Old FP = 0x1000

// Positive memory offsets relative to FP

.EQU VAR1, 0

.EQU VAR2, 4

.EQU SUM, 8

// Store old FP and LR pair, now SP at 0x0FF0

STP FP, LR, [SP, #-16]!

// Allocate stack

SUB FP, SP, #16

SUB SP, SP, #16

// Now FP == SP are both 0x0FE0

// Address 0x0FE0 - 0x0FF0 can be used

LDR W4, [FP, #VAR1] // W4 loads from 0x0FE0

LDR W5, [FP, #VAR2] // W5 loads from 0x0FE4

SUM W6, W4, W5

STR W6, [FP, #SUM] // Store sum at 0x0FE8

// Free Stack

ADD FP, SP, #16

ADD SP, SP, #16

// Now FP == SP are both 0x0FF0

// Restore old FP and LR pair, now SP at 0x1000

LDP FP, LR, [SP], #16.text defines immutable constants. .data defines mutable variables.

.fill directive is similar to calloc() in C, where addresses are filled with an initial value. .fill 255, 1, 0 fills 255 elements, each of size 1 and value 0.

.asciz defines ascii char array with null-termination. .ascii doesn’t provide null-termination.

X0–X7 registers are used for parameters.

X8 register is used for specifying service to call.

SVC 0 means introduce software interrupt to call the service.

Return code is saved in X0.

Calculate string size example:

inpErr: .asciz "Failed to open input file.\n"

inpErrsz: .word .-inpErr . means current address, so inpErrsz calculates current memory address – start of inpErr -> inpErr’s size.

Floating-point calculation introduces rounding errors over time, hence use fixed calculation in financial settings.

ARM FPU and NEON coprocessor shared registers:

V0 – V31 128-bit registers.

D0 – D31 is 64-bit double-precision version.

S0 – S31 is 32-bit single-precision version.

H0 – H31 is 16-bit half-precision version.

V0 – V7 are caller saved.

V8 – V15 are callee saved.

NEON coprocessor labels V0 – V31 as Q0 – Q31 for 128-bit integers.

NOTE with C

printf: When you use string substitution of"%f", C takes the floating point number starting fromD0–D31, instead of from the general register likeX1etc. The expected floating point format is alsodoubleprecision ONLY!Example:

// X0 has "%f\n" in message and D0 has a double floating point LDR X0, =message BL printf

Use FMOV to move between FPU registers and CPU registers

FMOV H1, W2 There are floating point versions of ADD, SUB, MUL, DIV, with F in the beginning like FADD.

There are also:

FNEG

FABS

FMAX

FMIN

FSQRT Sd, Sn // Sd = Sn^2FCVT converts between single and double precisions.

There are also instructions to convert between floating-point and integers. e.g.:

SCVTF Dd, Xm // Signed integer to double FP

UCVTF Sd, Wm // Unsigned integer to single FPConditional select and conditional increase.

// Xd = Xn if condition is true, else Xd = Xm

CSEL Xd, Xn, Xm, condition

// Xd = Xn if condition is true, else Xd = Xm + 1

CSINC Xd, Xn, Xm, conditionNEON coprocessor can process data in parallel with SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data). It divides the 128-bit register into different lanes, then process instructions in parallel between lanes.

Check out ARN website on the lanes concept: https://developer.arm.com/documentation/102474/0100/Fundamentals-of-Armv8-Neon-technology/Registers–vectors–lanes-and-elements

NEON coprocessor shares the same registers with ARM FPU. The instructions that apply to FPU is also for NEON. But the way to address register is slightly different.

{register number}.{lane count}{lane size}See page 293 and 300 on the book

Example to add 4 single floating point (128bit-wide) from V2 and V3 to V1:

// e.g.

FADD V1.4S, V2.4S, V3.4S

Leave a Reply